Who better to discuss gender politics than me, a wealthy, able-bodied, straight, white man?

Perhaps that shouldn’t matter. Ideally, we would approach technological and behavioural sciences with the academic objectivity they warrant. However, in the intersecting domains of sex and gender, it’s impossible to separate the author from the narrative. The term ‘sexual politics’ is apt: in matters as deeply personal as gender, the personal becomes political, and the political becomes personal.

Revolutionary Sexualities

Our species’ history is marked by revolutions. Climatic (the Ice Age), artistic (the Renaissance), and technological (Neolithic, or Industrial), all of our collective epochs are defined by significant cultural shifts.

We’re undoubtedly experiencing such a shift right now, although we can’t peer into the hazy future to determine what label will be assigned to our current period. We can’t predict the future, but we can learn from history’s lessons and speculate on what the accelerating evolution of technology might imply for gender politics, sex, tech, and sextech.

This is not an unrealistic ambition. We have examples of how technology has impacted gender politics in our recent past. Let me provide one specific instance.

The Industrial Revolution marked a change in how energy was extracted from nature. Previously, energy was wrested from the land by a robust man guiding a powerful horse. Now, energy was harnessed through science and chemistry: the feeding of coal into the gnashing, iron jaws of a furnace, for instance.

The Industrial Revolution’s introduction of threshing machines, construction cranes, and combustion engines sparked a sense of redundancy among Victorian men. Men were transitioning from physical labor to sedentary, office-based lifestyles.

This shift raised challenging questions about men’s identities. The expansion of capital-based international markets led industry leaders to invest heavily in education, aiming to create a literate and numerate segment of the workforce – industry needed accountants.

This created a persistent tension between the working class, primarily unskilled laborers, and the educated middle class, mostly financial and legal professionals. Today, this tension continues to be a pervasive force in society at large, and particularly in masculinity.

If this masculinity crisis sounds familiar, it’s because we never resolved it. Automation threatened the position of masculinity back then. Today, masculinity is threatened by information. The point, if it’s not clear, is that major technological advances invariably bring about upheavals in gender identity.

As a result, there was a re-evaluation of what it meant to be a man, and a desire to cling to muscle, and therefore strength, and therefore power. Contemporary marketing language targeted at men from that era is revealing; it extensively discusses virility and muscle, suggesting a growing fragility and uncertainty about men’s suddenly precarious place in the world. This insecurity likely contributed to the long-standing male reluctance to empower others, due to the perceived threat to their own power.

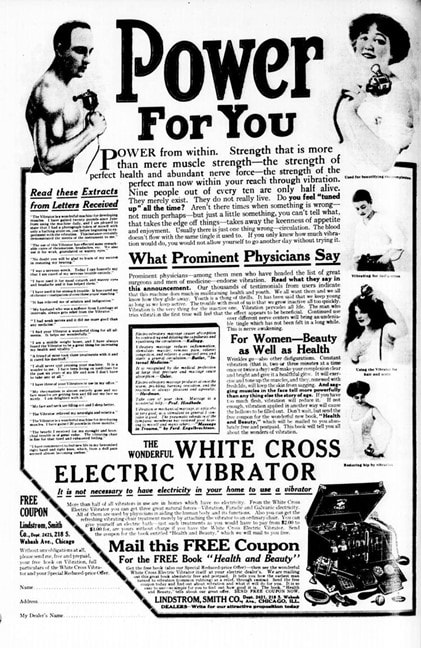

Below is a print ad from 1913 for the White Cross Electric Vibrator, one of the first commercially-available vibrators.

“Power for you.” “Power from within.” “Strength that is more than mere muscle strength.” This ad, and many others like it, extensively discuss concepts like virility and vitality, strength and power, catering to a male audience that felt increasingly disenfranchised and disempowered.

From the very beginning, what we now call sextech has mirrored, and then amplified, our anxieties about gender and identity. This was true in 1913, and it’s doubly true today.

So, with the understanding that sextech is a valid lens through which to view the future of gender politics, how might we anticipate sextech either reinforcing or challenging traditional gender roles in sex?

Reinforcing Stereotypes

When I mention “sex robot,” you might envision something akin to Alicia Vikander’s character in Ex Machina, or Pris from Blade Runner. If you’re in a playful mood, maybe the fembots from Austin Powers come to mind. Regardless, it’s likely an idealized, submissive, female-bodied automaton, even though the term “sex robot” doesn’t inherently imply any gender. The phrase “sex robot” could just as easily bring to mind a Dyson vacuum cleaner equipped with an artificially intelligent prosthetic penis.

However, it doesn’t. Why not? Because a sex robot is essentially the objectification of sex, and in our society, that role is often associated with cisgender women’s bodies.

Many experts in the field express concern that this conceptual image might become a self-fulfilling prophecy: if we collectively expect sex robots to look and behave in a certain way, that’s what will likely be developed, thereby reinforcing existing sexual stereotypes and traditional gender roles.

I’ve witnessed this development first-hand at the annual sextech expo in Shanghai, where the variety of sex dolls has become increasingly lifelike and communicative over the years. (In 2018, I asked one about the weather outside, and it responded in Chinese, “Today it is 32 degrees with 0% chance of rain,” before adding in English, “…baby.”)

However, it doesn’t necessarily have to unfold in this manner.

Subverting stereotypes

Rebecca Gibson, Associate Professor of Anthropology at Virginia Commonwealth University and author of Desire in the Age of Robots and AI: An Investigation in Science Fiction and Fact, shared with me, “Before the recent advancements in teledildonics and sex toys/sex robots that focus more on personal experience, there were essentially two options – a sex toy shaped like a phallus, or one shaped, to put it bluntly, like a hole. There was no acknowledgment of the clitoris or the need to stimulate body parts outside the penis/vagina binary.”

Dr. Gibson continued, “Now, there are sex toys that utilize sound wave technology or suction, which can be used without the toy physically touching the body. There are also workshops available to help individuals determine what would be best for their own bodies, expanding the user’s ability to choose beyond the previous binary options.”

The advancement of technologies like air-wave technology implies that sensations are no longer tied to specific anatomical structures. Mainstream cis-normative society often mistakenly equates anatomy with gender (penis = man, vagina = woman, etc.), but queer sextech has the potential to gradually disentangle this association by developing products that aren’t specific to any particular anatomy.

Thus, Dr. Gibson argues that sextech has the potential to be used in ways that aren’t tied to specific genders. However, the current market for sound wave or air pressure sex toys is dominated by brands specifically targeting women – notably, one of the largest of these brands is named “Womanizer.” Unless a major player in sextech takes the initiative to challenge the industry’s entrenched habits, gendered designs will only become more deeply rooted.

The case of men

Beyond the physical design of sextech products, there are more profound concerns. The gradual infiltration of AI into all aspects of the pleasure and sexual wellness industries brings both benefits and drawbacks. One of the more insidious ways AI is already having a negative effect is through hiring practices: numerous third-party Human Resources businesses now assist larger sextech brands in filtering job applicants using complex and opaque AI algorithms.

However, AI is not an innovative process, but a reflective one. The algorithms that power artificial intelligence rely entirely on existing data, and as a result, they merely replicate existing biases. Consequently, AI algorithms, due to the nature of their systemic input, tend to favor male candidates over female or non-binary ones.

This is why the majority of sex toy engineers and designers are male. This is why individuals like me, straight, able-bodied, white men who have never had a vagina, dominate an industry that primarily markets products to people who do have vaginas.

Of course, this isn’t the fault of AI. AI is merely a product of its programming, and in this case, it’s a reflection of the societal bias that values men in the workforce over women and non-binary individuals.

Our education systems tend to favor straight white men, not necessarily due to explicit policy, but certainly due to systemic biases. As a result, straight white men are more likely to be suited to available jobs, which may have been created by other straight white men, even if the primary market for these jobs is predominantly women.

I’d like to believe that the sextech industry is somewhat more progressive than mainstream tech and consumer goods industries, and that women and non-binary individuals have slightly better representation in positions of influence within our industry than in others. This may be an illusion or wishful thinking. Regardless, it’s clear how AI hiring algorithms could further entrench existing biases – for instance, men hiring men to develop products for women. This is a tangible, measurable way in which sextech could influence gender dynamics.

In other words, when it comes to the fundamental aspects of the industry, the decisions and strategies that shape the broader trajectory of the sextech industry, AI could simply perpetuate the status quo, but at a faster pace.

Dr. Gibson sums it up well: “If we infuse our AI’s programming with misogyny, racism, and inequality, and reinforce that by allowing some of the more toxic elements of society to use the AI regularly, we’re going to see those attitudes reflected in the outcomes.”

In the coding industry, there’s a phrase that aptly describes how poor input leads to poor output. It seems fitting here: “SISO” – shit in, shit out.

The sextech market

Perhaps the most potent tool for deconstructing and reinterpreting gender identity lies in the marketing of sextech products. For instance, while most current “sex robots” adhere to traditional gender norms, it’s encouraging to note that the popular X range from one of the main manufacturers, Realdoll, is modular. Faces and other anatomical features can be swapped out according to preference, providing some degree of freedom in gender expression.

It’s possible to imagine that sextech marketing can help to establish new frameworks in which gender is deemphasised in favour of a more conceptual and abstract understanding of sex and sexuality. Virtual reality, too.

By creating digital spaces in which sexual expression is unencumbered by physical limitations and presuppositions, we might stop seeing gender as a monolith, or as a binary, but instead understand each other to be sexual regardless of social conventions like gender.

Sextech and AI undoubtedly have the power to improve our lived experiences. I’m excited about the opportunities waiting around the corner for us.

But it needs some very human guidance along the way.

Leave a Reply