Trans people existed long before the trans tipping point emerged in the early 2010s, and trans video game characters didn’t appear suddenly overnight, either. While trans representation has increased over the past decade, trans and trans-coded characters have featured in video games since the 1980s: first as random non-player characters (NPCs), and then, increasingly, with their own minor and major character roles.

Today, trans people are gradually starring as protagonists, particularly in the independent queer game development world. But how did we get here? It’s a long and complicated story, and one, unfortunately, filled with complicated depictions of trans people along the way.

Early years: the 1980s to 2000s

Despite increasing coverage by games journalists and trans games critics, trans representation in games is an incomplete history. This is largely because queer game development during the 1970s and ‘80s is not well documented, and it’s highly likely that games historians don’t have full access to the breadth of independent queer games created during this time.

Even the first known queer game, C.M. Ralph’s 1989 point-and-click adventure game A Caper in the Castro, was lost for a time and only recovered in 2017. So any trans history of the games world cannot be treated as authoritative, but merely an account of known information at this time.

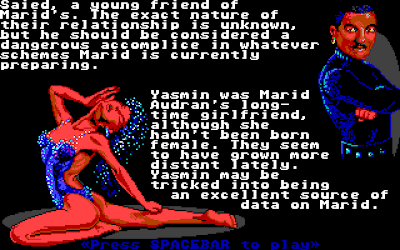

That said, trans characters’ representation in games dates at least as far back to the 1980s, if not longer. Technically, the first trans character from the mainstream Western games industry is transgender sex worker Yasmin, the protagonist, Marid Audran’s, ex-girlfriend in Westwood Associates and Infocom’s 1989 cyberpunk adventure game Circuit’s Edge. The characters of Yasmin and Marid both derive from George Alec Effinger’s 1987 novel, When Gravity Fails. The game Circuit’s Edge was a continuation of the story.

Early on in Circuit’s Edge, Yasmin’s gender identity is laid out for the player: “Yasmin was Marid Audran’s long-time girlfriend, although she hadn’t been born female,” as the game’s opening states. This is referenced again later on in the game, when the player first meets Yasmin, and the second-person narration proceeds to describe how “the only thing natural about Yasmin is her long black hair, which you consider her greatest asset.” This transphobic obsession with trans sex workers’ artificiality is a running theme in the game. In the fictional bar, Chiriga’s, players meet the post-operative trans woman sex worker Arissa Lockhart. The game notes that Marid “can see the subtle scars of extensive cosmetic surgery,” and that he wonders “how much of her is the original equipment.” Players can even learn of Arissa’s deadname and startle her with it, opening a dialogue route regarding her transition.

It’s not a coincidence that Yasmin and Arissa are transgender sex workers. Nor is it an accident that, according to Hardcore Gaming 101, many of Circuit’s Edge women are transgender. The game is tinged with subtle, yet pervasive, transmisogyny and whorephobia, often suggesting these trans sex workers’ bodies are unnaturally beautiful and thus deceptively appealing. And yet, Circuit’s Edge doesn’t hesitate to depict Yasmin and Arissa as desirable, at times objectifyingly so. In the game’s intro segment, for example, Yasmin arches her body for the player, showing her curvy figure as the game describes her relationship with Marid. Despite her trans status, she is made to be attractive to the player.

Early trans history in games is easily a story of contrasts in that regard. Take Birdo, originally introduced to Western players in Super Mario Bros. 2 in 1988. In reality, Birdo came from the Japanese 1987 platformer Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panic, which was rebranded with Mario characters and released outside Japan under the Super Mario moniker. In the original Doki Doki Panic, Birdo was named Catherine and preferred others call her ‘Cathy’, with the implication in the original Japanese that she “wrongly believes” this to be the case. When Doki Doki Panic was repackaged into Super Mario Bros. 2 outside Japan, the transphobia remained: the game’s manual changed Cathy into Birdo (although she was erroneously called “Ostro”) and said she “thinks he is a girl” and “he’d rather be called ‘Birdetta.’”

Over the years, Nintendo generally grouped Birdo in with female characters in party games like Mario Tennis and Mario Kart. But throughout Nintendo’s history, Birdo’s gender identity remained contentious and anxiety-inducing. In Super Smash Bros Brawl, for example, Birdo’s trophy describes her as “a pink creature of indeterminate gender that same say would rather be called Birdetta.” Birdo’s Japanese renditions are even more explicit in their transphobia; in her same trophy in Brawl‘s Japanese version, the game states she “firmly believes he’s a woman” and “gets extremely happy when people call him ‘Cathy’”.

To date, Nintendo has no clear, definitive answer for Birdo’s gender identity, leaving speculation up to fans and games critics alike. Similarly, no Nintendo game lists Birdo by either of her preferred names. Meanwhile, some trans players refer to Birdo as Birdetta instead as a sign of respect.

Birdo isn’t the only trans character with a complicated history by a befuddled developer. Poison, originally introduced in the 1989 beat-’em-up Final Fight, and later added as a mainstay in the Street Fighter fighting game series, suffers a similar fate due to her “indeterminate” gender woes. The dominatrix-themed Poison and another enemy, a palette-swapped version of her, named Roxy, were designated as “newhalfs” (a transphobic Japanese slang term for trans women) within Final Fight’s initial concept art, according to CBR.

Over the years, Poison’s trans status was increasingly hinted at in concept art and character bios released by Capcom, although this was generally left up to fan interpretation. That is, until Street Fighter IV producer Yoshinori Ono finally told Electronic Gaming Monthly in 2008 that Poison “is officially a post-op transsexual woman” in North America, and that in Japan, “she simply tucks her business away to look female.” (In 2011 speaking with EGM again, Ono concluded Capcom ultimately doesn’t have a stance on Poison’s gender, and that fans are left to their own interpretation to decide her gender identity.)

“[Trans characters’] few appearances [in the ’80s] generally relied on players outing or discovering NPCs’ gender identity as a transphobic punchline.”

Between Circuit’s Edge, Final Fight, and Super Mario Bros 2, the late ’80s revealed an industry passively thinking about trans characters and exploring (or in the latter’s case, stumbling across) trans-coded themes. However, Yasmin and Birdo aside, trans characters were rarely thrust into the spotlight as main characters throughout the ’90s and 2000s. Their few appearances generally relied on players outing or discovering NPCs’ gender identity as a transphobic punchline.

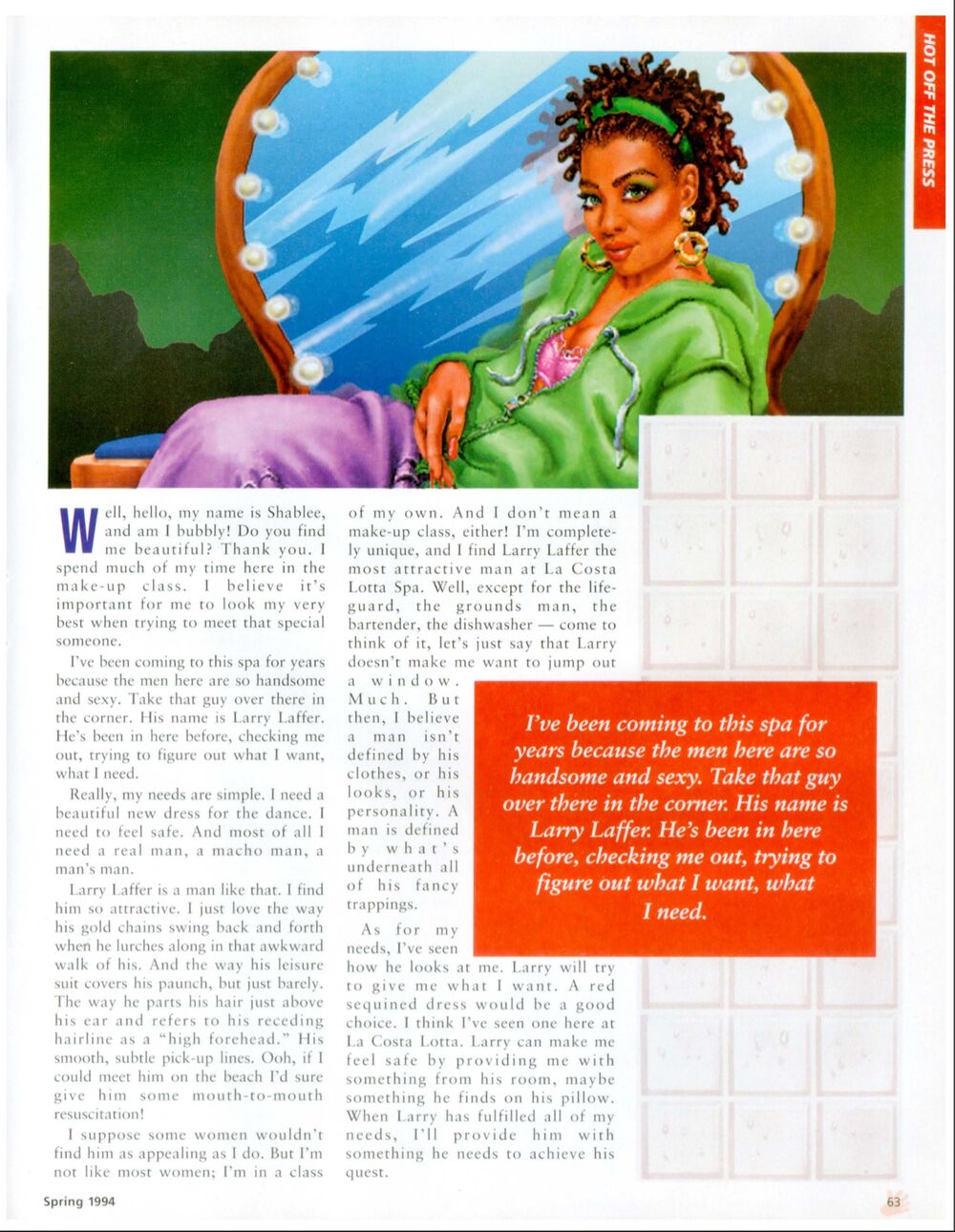

Released in 2006, Persona 3 features one scene where players meet a ‘beautiful lady’ on the beach who is surprisingly sexually forward. Shortly after, she is outed as transgender for having “hair on [her] chin” (along with another character shouting “SHE’s a HE!?”). A similar, far cruder “joke” plays out with Shablee, a trans woman of color in 1993’s Leisure Suit Larry 6: Shape Up or Slip Out! When Shablee goes out on a late-night beach date with Larry, her gender identity is revealed after she sports a bulging erection in her dress. The game implies Shablee sexually assaults Larry immediately after, completing the “joke”.

While these one-off moments were insulting enough, there were occasions where trans and trans-coded characters weren’t treated as a punchline, but a real threat to cisgender protagonists. One of the more transphobic iterations in the gaming community is Sierra’s 1993 adventure game Police Quest: Open Season (also known as Police Quest 4). The game’s main antagonist terrorizing Los Angeles is a serial killer who cross-dresses in women’s clothing in an apparent homage to Psycho and the 1991 film Silence of the Lambs. While the game does not outright state the killer is transgender, the transmisogynistic anxiety is obvious, down to the player character immolating the dress-wearing killer before they can butcher a bloodied woman lying on their bed.

Circuit’s Edge, Final Fight, Persona 3, and Super Mario generally dealt with microaggressions toward trans characters, but Police Quest and Leisure Suit Larry 6 represented something far more sinister during the ’90s: trans characters as predators, and character arcs ending in either desecration for the cisgender player character or death for the trans violator.

Granted, there were still notable exceptions to the rule during the ’90s and 2000s, such as Nintendo’s 2004 RPG Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door. In the original Japanese version, Vivian the Shadow Siren was depicted as transgender, and her fellow Shadow Siren sisters (one of the game’s main antagonists) commonly misgender her in order to insult her. Like Birdo, The Thousand-Year Door was not inherently trans-inclusive; even an in-game biography for Vivian misgenders her. But unlike Birdo, Vivian was overall treated as a sympathetic and lovable protagonist.

“During the ’90s, trans characters [were often depicted] as predators, and character arcs ended in either desecration for the cisgender player character or death for the trans violator.”

Granted, this storyline did not make the jump overseas during localization, even though her gender later became a known fact throughout the Western Paper Mario fandom. But it, once again, reveals the complexities of the 1990s and 2000s: bigotry in some games, sympathy in others. This would continue into the 2010s, but not without significant change.

Cultural Shift: The 2010s

During the 2010s, games’ relationship with trans characters started to shift into a far more inclusive, if not outright compassionate, direction. This was a slow, complicated, and ongoing process.

In 2011, Atlus introduced Erica Anderson, the transgender waitress in Catherine. Erica’s gender identity is regularly mocked by the game’s men and is used for laughs in a transphobic reveal during one of Catherine’s endings. But unlike the 2000s and ‘90s, even Erica’s writing was far more multi-dimensional than her predecessors’ depictions. Throughout the game, she appears as an average, everyday and amicable woman navigating adulthood, amid supernatural events. Despite her mistreatment at the hands of her childhood friends, Erica is not depicted as a monster, a predator, or a quick punchline: she is a person. After two decades worth of mediocre and one-dimensional trans characters, Erica was a surprisingly compassionate addition that represented a change in the right direction for trans stories in games, one bolstered by her fellow trans brothers, sisters, and nonbinary comrades over the decade.

Increasingly, far more compassionate trans characters appeared within video games from both the West and outside of it. 2012’s MMORPG Guild Wars 2 added Sya, a transgender aid worker who uses magic to aid with her gender transitioning, and 2013’s Pokémon X and Y famously added Beauty Nova, a transgender trainer who literally transitioned from an (all-masculine) Black Belt class into the Beauty class. Her Japanese iteration is even more explicit about her gender transitioning, referencing “the power of medical science”. By the mid-2010s, transgender representation became incredibly prominent, particularly in indie games, although trans characters have since appeared in in late 2010s and early 2020s AAA titles like Mass Effect: Andromeda, The Last of Us Part II, Assassin’s Creed Syndicate, Watch Dogs 2, and Horizon Zero Dawn.

So, what caused the change? In the West, numerous factors caused this shift. A sizable number of American and European independent queer and trans game developers emerged during the start of the 2010s. These creators developed ‘altgames’, artistically unique independent games with alternative gameplay that imagined new ways to write, depict, and explore transness through games.

One of the earliest and most influential examples includes Anna Anthropy’s 2012 Flash game Dys4ia, which examines gender transitioning and hormone replacement therapy from a trans woman’s perspective. Anthropy and other trans game developers turned to an HTML-based hypertext platform named Twine, where they created short, free, choose-your-own-adventure narratives easily playable on any modern web browser. Many Twine makers created works that centered trans experiences and encouraged trans storytelling. They also challenged the gaming industry to rethink gaming’s relationship with transness, and invited creators to develop more thorough queer representation in their work.

Meanwhile, another key actor shook the Western industry’s relationship with queerness: Bioware. The studio’s role-playing series Mass Effect and Dragon Age increasingly explored queer romance options. This set a higher bar for LGBTQ representation in games: it was no longer enough to have a gay or lesbian side character. Now, players should be able to engage in queer romance themselves during play. Bioware paved the way for a much larger conversation on LGBTQ inclusion in major video game releases—and, eventually, trans characters in both series too.

Cultural changes

As both of these phenomenons emerged in the games industry, another, larger cultural shift happened globally during the early 2010s. Across mainstream media and entertainment, the world became far more cognizant of trans issues as celebrities such as Caitlyn Jenner, Laura Jane Grace, Lana Wachowski, and Janet Mock came out. Transgender actress Laverne Cox rose to stardom in her role as Sophia Burset in 2013’s Orange is the New Black, and three years later, backlash to North Carolina’s trans bathroom panic law “Public Facilities Privacy & Security Act” (also known as HB2) drummed up widespread support in the US for trans rights. These same cultural conversations served as a catalyst for trans representation in video games, and introduced a far more widespread interest in sensitively depicting trans men, women, and nonbinary characters across the industry. By the mid-2010s, trans representation was far more prominent than ever before.

However, there were still some major mishaps in the 2010s. In Beamdog’s Baldur’s Gate: Siege of Dragonspear, an NPC named Mizhena randomly divulges her trans status to the player, seemingly for no other reason than to explain why her name is so unusual. In an even worse example, Mass Effect: Andromeda‘s Hainly Abrams randomly discusses her gender identity and divulges her deadname to the player for no discernable reason. These situations were intended to be inclusive and affirming, but they were still rooted in cisgender obsessions over transness that resulted in stilted, lifeless, and unrealistic trans characters. Both Bioware and Beamdog later patched these issues in their works, but not before public outcry from trans players.

But not all games failed to handle trans representation properly. Despite Bioware’s problems with Mass Effect: Andromeda, Dragon Age: Inquisition’s Cremisius ‘Krem’ Aclassi was universally praised by trans players as a realistic and thoughtfully written transgender man. This wasn’t by coincidence. In a blog post from 2014, Bioware’s Patrick Weekes explains that Krem’s writing was vastly improved thanks to sensitivity feedback from genderqueer friends.

And while the AA and AAA games world grappled with trans representation, independent game developers led and informed by the trans community generally fared far better with creating nuanced trans characters. Cyberpunk adventure games Technobabylon and The Red Strings Club, released in 2015 and 2018 respectively, both feature nuanced trans women as minor characters. In Technobabylon‘s case, transgender police officer Max Lao believably depicts a trans woman’s life in a speculative, trans-inclusive cyberpunk future (Max’s depiction stemmed partly from trans peoples’ input). Meanwhile, The Red Strings Club offers Larissa Robillard, a marketing director who generally has a pleasant life in the cyberpunk future, save for a scientist at her company who stores her deadname as his computer password.

At the time, the deadname puzzle was criticized as transphobic by Vice. But in hindsight, this in itself was a commentary on cis men’s possessiveness toward trans women, as one of Deconstructeam’s developers, a transgender woman named Paula Ruiz, explained to Vice. Even in divisive moments, trans input ultimately led to far more nuanced conversations on issues impacting trans players in the real world, compared to Mass Effect and Baldur’s Gate’s obvious faux pas.

“We agree it’s important to talk about all this stuff and denounce it, but it’s also important to look at all angles of a story,” Ruiz told Vice. “About deadnaming itself, I just want to say that even if deadnaming really sucks, it’s a thing I have to live with as I’m still early in my transition and in the country where we live I still have lots of months of waiting until I can legally change my name. Deadnaming sucks, but it’s also a part of trans people’s realities, and the game tries to capture that bit too, maybe not in the depth it should according to you, but at no moment was its use frivolous.”

“It was queer and trans developers that demonstrated the road ahead for trans representation, not necessarily the biggest studios in the games industry.”

Queer developers continued to lead the charge for better representation during the mid-to-late 2010s. We Know the Devil and Heaven Will Be Mine, two popular queer visual novels by Pillow Fight Games, each feature transgender women as main characters. Their relationships with other characters do not hinge on their gender, and yet their relationship with their gender identities weaves throughout each narrative. Similarly, GaymerX’s subsidiary game development studio MidBoss radically pushed the envelope for what trans representation could look like for both binary and nonbinary trans people with 2064: Read Only Memories. The studio not only gave the player the opportunity to choose their own pronouns (including custom ones), it also introduced several trans characters as part of the game’s main roster. Just like the early 2010s, it was queer and trans developers that demonstrated the road ahead for trans representation, not necessarily the biggest studios in the games industry.

Looking forward: Trans characters today

Today, gaming’s relationship with trans characters sits at a complicated crossroads. Games like Dontnod Entertainment’s Tell Me Why and Celeste are part of a growing trend of video games that canonically place trans characters into lead roles. Even CD Projekt Red’s Cyberpunk 2077, largely panned for its transphobic ‘Chromanticore’ ad, offers players the (ironically) revolutionary ability to customize their characters’ genitals regardless of their gender. However, trans main characters remain the exception to the rule, and many games do not make room for trans experiences at all. Video game characters are treated as canonically cisgender de facto until proven otherwise.

While the mainstream games industry still has a long road to go, the independent games industry continues to blaze a trail forward. ValiDate, an upcoming visual novel with a QTPOC cast, includes a bigender trans feminine lesbian love interest named Emhari Abdi. In Japan, visual novels One Night, Hot Springs and Last Day of Spring from producer npckc explore the intricate challenges transgender women face navigating daily life in Japan. Affirming, heartwarming indie games like Lookouts and Girl Things cherish the unparalleled love trans-masculine and trans-feminine people share for each other, respectively. Meanwhile, avant garde titles such as Glamow Research’s The Trans Zone feature overstimulating 3D worlds that explore the complicated, disorienting feelings and experiences that come with gender transitioning.

Indie adult games also offer increased visibility for trans players. Nadia Nova’s trans-sapphic Twine games offer immersive worlds for queer trans-feminine people to find erotic longing and desire because of their bodies, not in spite of them. And bigger, ambitious independent adult games like Dominatrix Simulator and Hardcoded feature transgender protagonists, with the latter starring a predominantly trans cast – a rarity in the 18+ games world.

The mid-2010s’ awkward days are still here, to be clear, and transphobia is not going away any time soon. But the industry as a whole looks far more inclusive than it did during the turn of the century largely due to the steady, growing space available for queer and trans independent game developers. It’s a promising sign for trans players, who just want to play games where they feel seen, understood, and respected, while in their favorite fantasy worlds.

Read Next: Queering industry: How LGBTQIA+ businesses are trans-forming tech

Leave a Reply