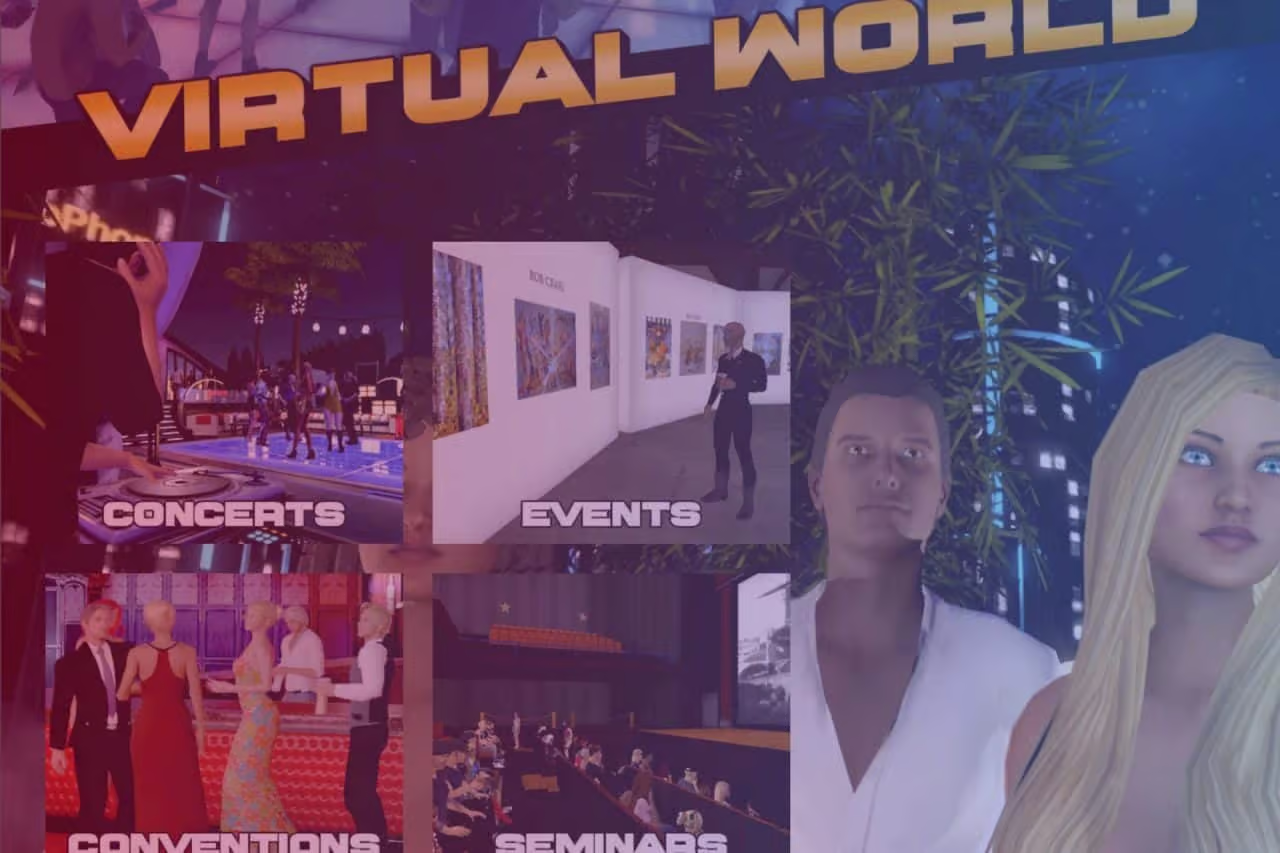

If you use a female-presenting avatar when entering a metaverse space, it’s usually not long before a penguin or elf or… whatever avatar begins groping, humping, or otherwise harassing your pixelated persona.

Unwanted sexual behavior in metaverse spaces is a massive problem, but should behaviour like this be criminalized? And should we stop calling this stuff ‘virtual’ behaviour, and treat it as ‘real-world’ harassment, attacks, or even in some cases, rape?

The authors of a new academic journal paper answer ‘yes’ on both counts. Law professor Clare McGlynn and law and digital technologies post-doc researcher Carlotta Rigotti have made their case in a new paper called ‘From Virtual Rape to Meta-rape: Sexual Violence, Criminal Law and the Metaverse‘, published in the Oxford Journal of Legal Studies.

McGlynn and Rigotti analyzed past cases of alleged sexual abuse and harassment committed by human-controlled avatars in metaverse spaces, and are campaigning for the use of a new term: ‘Meta-rape’.

They argue that many people use phrases with the word ‘virtual’ when describing behavior like this, which minimizes its real-life impact. They define meta-rape as “all forms of non-consensual intrusive conduct of a sexual nature in the metaverse, committed by or experienced through an avatar”.

Although there are plenty of adult content-focused metaverse spaces, most mainstream metaverse spaces ban nudity and overly-sexual appearances and behaviour. Still, that doesn’t stop users making their avatars behave in sexually aggressive ways, sometimes to the point of avatar ‘gang rape’.

In 2024 the case of the avatar of a girl under the age of 16 being allegedly ‘gang raped’ by avatars in a VR game was investigated by police in Britain. Officers said the girl suffered the same psychological trauma that a rape victim in the ‘real’ world would have felt.

With ever-improving VR technology designed to make users feel that they are indeed operating in the real world, the case that behaviour within VR spaces should be treated as if it took place in a non-VR setting is getting stronger.

A new term for VR sexual harassment?

The paper’s authors said that metaverse space avatars should be “understood as ‘externalised projections of their users’ regardless of the ways in which that avatar is presented.”

They added that the word ‘virtual’ should be ditched in this context, and that the new term ‘meta-rape’ “describes the nature and extent of the harms being experienced, predominantly by women, as well as recognising the seriousness of the abusive behaviours.”

They pointed out that discussion about ‘virtual rape’ dates back as far back as 1993, in the virtual world LambdaMoo, in which a user allegedly used a text-based program to coerce other users into having their avatars behave in sexual ways.

Since then, ‘virtual rapes’ in metaverse spaces such as Second Life and Meta’s Horizon Worlds have made headlines.

The researchers wrote: “Sexual harassment and sexual violence in the metaverse are tangible, lived experiences, with real-world, physical ramifications: it is simply another version of reality, where users identify with and embody their avatars, considering them as extensions of themselves while engaging emotionally in social interactions.”

Time to criminalize VR sex attacks?

How do you begin to approach enforcing the criminalization of behaviour within a metaverse space? Many such spaces offer a large degree of anonymity, with users able to log in from anywhere in the world with an internet connection.

The researchers did not suggest how criminalization could be implemented, but argued that some metaverse acts could be considered sexual crimes under the definitions of current laws. The use of haptic technology had blurred the lines of what could legally be considered touch, they argued.

One way could be to crack down on metaverse space providers such as Meta, rather than just individual avatar users, to encourage them to take unwanted sexual behaviour in their spaces more seriously.

For now, though, McGlynn and Rigotti want to see a paradigm shift in which it becomes accepted that VR technology has made the experience of metaverse spaces so realistic, that it’s logical to consider them ‘real’ on a moral and legal level.

They wrote that their aim was to “disrupt conventional thinking by addressing the gendered nature of these forms of abuse and their dismissal as not ‘real’, providing an umbrella framework within which new experiences and modes of perpetration can be located and accurately understood as abusive.”

Leave a Reply